For my first blog post I would like to elaborate on a similarity I noted briefly in class between Godard's realization of Trufautt's treatment for Breathless, and the way in which jazz musicians use what is known as a “lead sheet” as a springboard for improvisation. For the benefit of those not acquainted with modern jazz music, I will use a well known and easily accessible piece as reference: Miles Davis' “So What,” from the classic album “Kind of Blue,” which was also recorded in 1959. (An interesting aside: before recording “Kind of Blue,” Davis performed the score for Louis Malle's 1958 film Ascenseur pour l'échafaud (Elevator To The Gallows), in which he was asked to improvise music to the mood of the sequences as they were screened for him.)

A “lead sheet” is a usually one or two page piece of sheet music which contains the basic skeletal elements of a given composition, especially a piece of “standard” repertoire. Often there is enough of a shared vernacular in repertoire that jazz musicians will not need to reference the music but as a rule, the lead sheet contains the basic musical information on which the musicians will base their performance. Typically a lead sheet contains only a treble clef while others include both treble and bass clefs, if the composition features a written bass part. Similar to classical theory's “figured bass” notation, jazz musicians refer to “chord symbols” to know for what duration of time any given chord center is lasts. The majority of the time, bassists and pianists refer to these chords symbols to improvise their support during the reading of the melody, and all players use this information as a starting point in their solos. Typically, jazz compositions cycle back to the beginning of the lead sheet once they've reached the end of the form (i.e., the end of the lead sheet); this way, any given soloist may improvise for as long as they please within this form and may finish with the next soloist ready to begin. A typical lead sheet or “chart” for a standard piece of repertoire might have as many as 10 chords, each functioning in their own to compose the chordal progression (or “changes”). It is important to note here that Davis' “So What” only has two chords for the entire 32-bar form: two 8-bar sections of D-minor, one 8-bar section of Eb-minor, and the one last 8-bar section of D-minor.

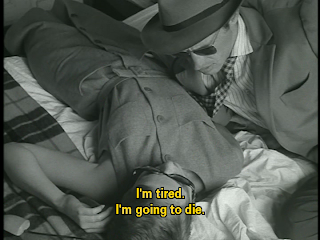

Below is a lead sheet for “So What,” along with a YouTube video which contains the original recording in its entirety. Note that the composition begins on the page when the (now famous) bass figure begins. There is a short piano/bass introduction on the recording which was written by Gil Evans, though it was not credited. The melody proper begins around 33 seconds and the improvisational sections begin at 1:32. Note the essential form of the composition during the improvisation sections is represented here by the tiny chart on the lower right side of the page. Below this, I have included stills from the lengthy hotel room scene in Breathless, along with the words from the treatment, as an analogue to the idea of the lead sheet. Indeed, any part of the treatment's translation into the film could be focused on in this way, but it is this sequence that most reminds me of the idea of jazz improvisation; of the translation of a simple idea into the sublime – even more so than the rhythm produced by the jump cuts during the films more kinetically edited moments.

What I find truly remarkable is the similarity here between the creative processes of jazz musicians like Miles Davis and the way in which Godard (as well as other filmmakers) bring to visual life the words from an original treatment. This is precisely what jazz musicians do-except the translation is to sound, as opposed to image.

As the 1960s unfold, Davis will revisit “So What” many times in live performances and the composition will undergo dramatic changes in treatment, tone, and unpredictability. Each progressive performance of the tune yields surprises. There is a similar feeling in Breathless – that if Godard used the same treatment as a starting point to make the film once again, what would result is a similar aggregation of chance, form, and rhythm, but a qualitatively different cinematic performance. Breathless was born of the circumstances of its production, just as Kind Of Blue was born both from loose concepts formed apriori as well as the moment of inception. In a sense Godard is like a jazz musician “riffing” on a kind of cinematic “lead sheet” throughout his early work: the Hollywood genre film. Using these cinematic templates as a starting point in films like Breathless, Pierrot Le Fou, Alphaville, and A Woman Is A Woman, Godard lets the process of discovery lead to the film's birth, and it's this art as process that he shares with contemporary modern jazz music. Is this not the same process of discovery that is felt when John Coltrane is heard at 3:25 on “So What”? There is a direct correlation in the process of translating the (in this case very scant) harmonic information on the page to the sublime level of Davis and company, and the translation of bare bones treatment in Breathless.

I will pursue this relation between movements in modern jazz and Godard's films – as well as art cinema in general – either in my next blog post, or as a presentation later on in the semester. Of particular interest is the “free jazz” movement marked by Ornette Coleman's mercurial arrival in New York in 1959. John Coltrane will also go on to play a pivotal role in this movement.

- Ian J

- Ian J

I apologize for the low quality stills-the version of "Breathless" I own is a really bad transfer, sub-Criterion.

ReplyDeleteTerrific post, Ian. It's even better when you play the Davis' piece as one scrolls down the entry, especially the frame grabs (which go quite well with the music). I think the analogy between free jazz and Godard is a good one. Of course, someone might object that the difference is that however spontaneously Godard shoots his films there is the postproduction stage where the piece is assembled, and where order is restored. They would be right to point this out but we should not forget – I'm sure you will remind us – that jazz also has its "postproduction" phase. Here I think in particular of the collage-like structure of Davis' In a Silent Way, one of my all-time faves. In both cases (Davis and Godard), structure and improvisation are made to function like two sides of the same coin.

ReplyDeleteSam

Ian,

ReplyDeleteI was really intrigued with your comments in class on the parallels between jazz and Godard and am glad you continued it in the blog. Question for you, "Kind of Blue" has always fallen under the description as modal jazz. What you are describing sounds like modalism (mode instead of chord based music). Is it the same?

Anyway, this is the oft repeated story about the album but it bears resemblance to Godard's on set approach to actors that Miles did not call for rehearsal and the musicians had little idea what they were to record until just before the tape was rolling.

Two days, Six musicians recording onto three track tape machines yielding five great stereo songs. Amazing.

Chris

Chris,

ReplyDeleteSorry it took me so long to respond! You're absolutely right in pointing out the similarity in directing style between Davis and Godard. Coincidentally, I am planning a paper on the need to understand the idea of the auteur in the context of jazz, using Miles Davis' 3 great quintets (or sextet, in this case) as examples. Jazz is often misunderstood as an artform in which 5 or 6 musicians assemble and with no direction, begin playing. Fair enough, this does happen-but as you know, an album like "Kind Of Blue" is more than a chance encounter, it is lead by an a singular creative force, even if the ideas employed are abstract. The same goes for the albums Davis will record in the 1960s-especially "In A Silent Way," which Sam noted as being one of the first examples of the cinematic idea of "post-production" as applied to jazz music.

Also, "Kind Of Blue" is the quintessential modal jazz album (excluding "Freddie Freeloader," which while classic is not strictly a modal blues piece-although one can't imagine the album without it.) I hesitated to explain modal jazz in the post as I didn't want to bog down further an already abstract concept to understand. "So What" in specific is an example of modal jazz par excellence as it has literally only two tonal centers for the entire 32-bar form. Jazz musicians of the period (and today) refer to modal improvising as being more "vertical," and standard repertoire as more "horizontal," as the latter's emphasis on a series of passing chords asks the improviser to acknowledge these frequent cadential changes-which seem to have a forward momentum.

-----------

Sam,

As I mentioned in response to Chris, you're right in pointing out that jazz recording of the period did not have the same extensive post production period that cinema did. However, while not entirely the same thing, jazz musicians still had the option of using different "takes" of a given composition, thus enabling a bandleader to select the take they think best showcased the performances of band. It's interesting here to listen to the numerous CD reissues of with included extra takes and try to find out why a given performance was deemed unusable or undesirable.

This does change with producer Teo Macero becoming de facto "editor" for Davis when he begins recording voluminous amounts of tape during marathon recording sessions. In fact, as jazz moves into the 1970s, the post production process will become more and more important as studio albums begin to be recorded autonomous from the music's live counterpart. The band Weather Report (co-led by Davis alum Wayne Shorter) was exemplary of this shift.