Sunday, October 31, 2010

We meet, we see a movie, we eat, and maybe we have sex

I find that Godard is at his most powerful and perhaps even his most radical in the moments when he is able to capture real and honest human interaction. For myself, it is these small moments, these intimate conversations, these glances and touches that provide a framework from which the viewer, as a human being, can truly connect with the film, with Godard, with existence. These small moments that we so often overlook, coffee swirling in a coffee cup, arguing with our partners about intimacy or the absence of intimacy, the leaves blowing in the wind, or dancing alone to our favorite song are the defining moments that connect us to one another and that represent our shared experience and emotions.

The clip from 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her at the garage when the camera ends up focusing in on the tree, the sunlight, and the leaves, calls to mind this scene from The Hours when the character, Richard, a poet played by Ed Harris, is talking about his simultaneous need and inability to express what his life has meant.

Richard is debating a similar topic as the one to which the narrator in 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her is asking: how is it possible to communicate our day to day experiences? It is the same task the camera takes up in focusing not solely on the action of the characters but the reflection of the sun on the hood of the car, a child crying, and the daily routines at a hair salon. Although Godard was/is inspired and motivated in his work by politics and current social happenings, I would argue that it is not necessarily in his overt political messages or blatant criticisms of consumerism and society that set him apart as an artist and a director. Rather, it is the apparent ease and consistency with which he is able to show us what our lives look like and why we should pay closer attention.

-AB

Halloween Weekend

Zombie bourgeois murderers, kids dressed as Indians, twisted corpses of burning cars and human bodies, Emily Bronte and Tom Thumb in the forest, the son of God and Alexandre Dumas pulls a rabbit from a glove compartment, cannibal hippie revolutionaries nonchalantly eat flesh...it’s a Halloween Weekend.

|

| The horror! |

|

| Worker, bourgeois brat, just another exchangeable costume, |

Harun Farocki reads this moment as one in which there is an acknowledgment of the “desire for absolute value” which disappears as we realize the river is not “the domain of the gods...but a little watering hole where families go to swim.” While I agree that this rupture is contained and ultimately unsustainable, I also read it as the suggestion of the potential call to a return to year zero that Godard speaks of. A return to year zero is also a terrifying possibility. What would it entail? This is not a moment of redemption, no matter how much I might want it to be, but the primal sound of the drum and call to the river remind us—briefly—of a different state of being, or a place of origin. And yet, the incantation is spoken with the same indifference as Corinne’s recounting of her sexual adventures, the same indifference with which Roland allows Corinne to be assaulted.

The river is not portentous—again, there can be no deep symbols here. As we read in Godard on Godard, the sea in Pierrot Le Fou and Le Mépris is not the sea of the gods, but just “nature, the presence of nature, which is neither romantic nor tragic” (219). Perhaps this is why in Weekend, the river retains some charge, because it simply is, pre-existent, the same and yet always different.

Following this incantation, we come to the final scene in which Corinne eats Roland’s flesh, another moment that could be ritualistic but, as Silverman and Farocki point out, is devoid of meaning or sacrifice (107). This scene communicates the trouble facing any revolutionary movement: by employing the violence of the oppressive regime of consumption, you open yourself to the possibility of becoming another version of the same. It’s far too easy. After all, you are what you eat.

-Ruchi Mital

Friday, October 29, 2010

Reappropriaton - "CNN Concatenated" by Omar Fest

I also wanted to share this a couple weeks ago, but couldn't find the link to it. An interesting example of reappropriation of network news footage which is used to by the artist Omar Fest to reveal a hidden narrative beneath such programs, as well as to reveal the stage-managed mannerisms and codes of cable news in general. Since I am not familiar yet with Godard's digital and television work, I'm not sure if the work has a specific aesthetic parallel, but its imaginative use of montage to create a new meaning out of existing ubiquitous material would seem related to Godard's own aesthetics and desire to probe the nature of image in society and history.

To "concatenate" means literally to link or connect through a chain or series. This is relevant both in the artists formal choice, as well as to the nature of montage and editing in the cinema, and its potential ability to subvert existing images through selective concatenation and ordering.

The Youtube user disabled embedding, so you will have to open the link in a new window to view the video.

"CNN Concatenated" by Omar Fest

Ian

To "concatenate" means literally to link or connect through a chain or series. This is relevant both in the artists formal choice, as well as to the nature of montage and editing in the cinema, and its potential ability to subvert existing images through selective concatenation and ordering.

The Youtube user disabled embedding, so you will have to open the link in a new window to view the video.

"CNN Concatenated" by Omar Fest

Ian

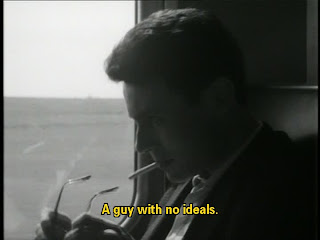

A Guy Without Ideals – Initial Thoughts On "Le Petit Soldat"

I will not undertake a complete plot and story summary here, suffice to say protagonist Bruno Forestier (Michel Subor) is an Algerian war deserter who has become a secret agent for the French military in Geneva, Switzerland – the city perhaps chosen allegorically by Godard for its historical neutrality in world conflicts. After aborting an assassination attempt, Forestier becomes suspect in his allegiances and is subsequently kidnapped and tortured by an Algerian terrorist cell. The entire film features voiceover by Forestier, recounting his thoughts a posteriori.

Le Petit Soldat is an interesting entry in Godard's ouevre. His second film, it is both a continuation and a departure from the themes explored in the kinetic cinematic celebration that is Breathless. Although the film is political in both form and content to use Comolli/Narboni's terms, there is little here that foreshadows the kinds of politicized films we are now considering in class. The blunt depiction of torture (which resulted in France banning the film until 1963) is provocative and disturbing, yet its effect intentionally undermined by the Bruno's voiceover. On the other hand, despite the film looking very similar to Breathless – i.e., jump cuts, shooting on location – the tone and focus shift squarely on the existential ennui of Bruno Forestier. If anything, Michel Poiccard's existential queries are the main thematic link between Breathless and Le Petit Soldat.

The setting of Geneva is also significant. As Douglas Morrey notes, Geneva is a city apart: too Swiss to be considered French, and too French to be considered Swiss. Forestier's voiceover describes the city being divided by two lakes. The film then can be a read in terms of a grey area between two defined regions, politically and metaphorically speaking. This ambiguity extends to the soundtrack, composed of dissonant piano music that refuses to resolve to either major or minor tonality – or any certain tonality at all.

Le Petit Soldat is essentially dealing with a world in which Bruno does not fit – he is asked to perform tasks to which ends he does not subscribe to and suffers the consequences for not completing these tasks – at the hands of both the French secret service and an Algerian terrorist group. We never learn why he deserted, although it isn't hard to venture a guess. As he describes himself in voiceover, he is a man without ideals, and is constantly questioning the nature of his existence. This in turn complicates his relationship to the world around him. The voiceover divulges his ambivalence toward the situation at hand – even when he being tortured by his Algerian captors he admits via voiceover that he doesn't even know why he is withholding the information being asked of him.

Forestier's hesitation to kill his target reminds me of Meursault in Albert Camus' The Stranger, which is set in French Algiers. The indifferent murder of the Arab man by Meursault is now replaced by the irrational indifference to the political/military aim represented by Bruno's assassination attempts. Perhaps this comparison is too forced though, as Bruno (and Godard) later dismisses Camus during his long speech at Veronika Dreyer's apartment, and in fact does end up assassinating his target with the voiceover suggesting that he has come to a personal awakening of sorts.

Anyone familiar with the work of director Claire Denis will recognize the name Bruno Forestier from Claire Denis's Beau Travail. Denis appropriated the character (also played by Michel Subor) as head of a small French Foreign Legion unit stationed in Djibouti. The force's presence and their barracks are an anachronistic vestige of France's imperial ambitions in the region. Denis' concerns with the outsider are of relevance here as the film resonates a similar kind of existential isolation. The film contains numerous allusions to Le Petit Soldat, which I will post soon as my Beau Travail DVD isn't working at the moment. It's important to note here that these allusions are not solely referential but constitute a thematic link between the two films: the lost ideal and the political, psychological and moral quandaries that accompany this state.

More stills soon!

Ian

Thursday, October 28, 2010

Godard's Tracking Shot

Godard's use of the tracking shot adds a new dimension on how we view his films, especially in the case of Weekend. Throughout the film we are permitted a certain amount of distance from our main characters. There are a few moments where we are permitted closely framed view of Corinne and Roland. In “Toward A Non-Bourgeois Camera Style, Brian Henderson writes, “A camera moves slowly, sideways to the scene it is filming. It tracks. But what is the result when its contents are projected on a screen? Is it a band or ribbon of reality that slowly unfolds itself. It is a mural or scroll that unrolls before the viewer and rolls up after him"(425). We are allowed to truly read this film in our personal way, choosing which direction the text should move as the camera tracks left and right. When watched the scene where Corinne and Roland are trapped in traffic, it’s oddities become personalized through the set of images appearing as the camera tracks.

Link to the traffic scene in Weekend: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8ScGLdfqdYo&feature=related

The flatness of Weekend is paralyzing and also energzing, “Godard presents instead an admittedly synthetic single layered construct, which the viewer must examine critically, accept or reject. The viewer is not drawn into the image, nor does he make choices within in; he stands outside the image and judges it as a whole" (425). The meaning Godard creates is multi-faceted, our "judgement" depending on our own code of ethics and principals.

Inside the factory in Tout Va Bien

Another interesting use of the tracking shot is in Tout Va Bien. While we are in the factory, there are a few moments where Godard creates a canvas out of his set, and we are able to stand on the outside, and make our conclusions, especially with the relationships we are allowed to see spatially. This specific moment in Tout Va Bien reminds me of how Wes Anderson sometimes allows to view his interiors as a flat canvas. He did this in The Aquatic With Steve Zissou, and I feel like this is something he borrowed from Godard. Like in Tout Va Bien, by showing us the characters in their habitat's gives us a sense of their relationships to one another and the space we're in.

VM

Wednesday, October 27, 2010

Pierre Clémenti and May '68 in Color

One of the figures associated with the Zanzibar Group was the actor/filmmaker/agitator Pierre Clémenti. He worked with a number of great filmmakers in the late sixties/early seventies, including Pier Paolo Pasolini, Bernardo Bertolucci and Luis Buñuel (in probably his most memorable role as Catherine Deneuve's thug lover, with gold-capped teeth, in Belle de jour). Here is Clémenti in Le Lit de la Vierge one of the films of Philippe Garrel, probably the most important filmmaker of the Zanzibar Group. It has music by Nico (of Velvet Underground fame), who was Garrel's lover. That's her too at 1.40.

Clémenti also shot footage himself of the May '68 riots – and in color. Here is his film he made of this footage, entitled La Révolution n'est qu'un Début: Continuons Le Combat.

Clémenti also shot footage himself of the May '68 riots – and in color. Here is his film he made of this footage, entitled La Révolution n'est qu'un Début: Continuons Le Combat.

Sunday, October 24, 2010

The Unseen Speaker

There is an image in many of Godard’s films where the face of the speaker is in some way obscured. This is different than narration where the audience expects never to see the speaker. It is more similar to Godard’s method of talking through an eyepiece and having the actor repeat what he says; though we see the actor’s image transmit the dialogue, it originates from an unseen speaker. Even if the speaker is not unseen, his/her face is often covered. I am trying to understand the role and impact of the unseen or obscured speaker in three ways, 1) a method used by Godard to demonstrate, as Douglas Morrey says in Jean-Luc Godard, “the violence which accompanies the process of learning.”(pg.68) 2) the attempt, as Godard says in Godard on Godard, to show how a person sees “what surrounds him.” (pg 241) and 3) the Brechtian alienation effect as described in Bernard Dort’s “Towards a Brechtian Criticism of Cinema.”

The first idea is from Morrey and I take it to mean that Godard’s use of an unseen speaker can be understood as a device which explores the idea of learning and knowledge by not giving the audience an image he/she can relate to within the given context or is expecting at all.

Rather than present us with images, sounds and ideas that can be immediately recognized and assimilated to our pre-existing categories of understanding Godard forces us to confront the difficulty of making sense of the world, the violence which accompanies the process of learning. Often Godard will cut into an image or a sound that is not instantly recognizable and presents us with a pure, inassimilable difference.

The above image from 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her can be an example of the first theory. The faces of the speakers covered and replaced by travel bags with logos on them achieve the end of difference and chaos in understanding what is happening.

In the second idea, Godard’s own analysis from Godard on Godard (pg. 239-41) refers to his strategy for creating 2 or 3 Things I Know About Her:

I cannot avoid the fact that all things exist both from the inside and the outside. This can be demonstrated by filming a house from the outside, then from the inside, as though we were entering inside a cube, an object. The same goes for a human being, whose face is generally seen from the outside. But how does this person himself see what surrounds him? I mean, how does he physically experience his relationship with other people and with the world?

In Weekend, two laborers stop to eat sandwiches. The face of the actual speaker is replaced with the face of a different man eating a sandwich. The speaker is not seen as he gives a lengthy speech about war and injustice; the audience only sees the face of a different man eating a sandwich. (To see this scene, click on the link below.)

This seems to exemplify Godard’s desire to show how humans physically experience seeing the world around them. When we talk, we do not see ourselves talking; we see the person we are talking to, even if he is eating a sandwich.

The third idea is from Brecht as Dort describes his alienation effect as that which “allows us to recognize its subject, but at the same time makes it seem unfamiliar.” (pg. 238) And although Dort is skeptical of this working in the world of cinema (as opposed to theater), Godard seems to use this very method in La Chinoise, most obviously in the scene depicted below. (Jean-Pierre Leaud explains his idea of Brechtian acting as demonstrated by a Chinese protester.)

These three ideas may intersect and there may be more or better examples than the ones I give above. However, I hope that this explanation of the unseen or covered speaker begins to address an image that has been repeated and expanded on in many Godard films.

Sienna

Thursday, October 21, 2010

On 'Heterotopia'

Heterotopia.

{In response}

This film/video work is an attempt to design a succinct example of heterotopia as defined by French philosopher, Michel Foucault {Of Other Spaces, 1967}.

To paraphrase:

In opposition to the inverse relationship to reality that is utopia, a heterotopia is an immersive virtual space, an intermediate flux {a space of otherness, neither here nor there, simultaneously physical and mental} that both reflects and alters the experience of the lived environment in which it is found.

=

This piece seeks to engage the aforementioned properties on three principle levels in an exploration

of storytelling through non-linear modes of interpretive pairing in image and narration.

• 2-dimensional projection in 3-dimensional space.

{In its ideal form, I would like to project this video on to a suspended, transparent surface so the viewer may explore both direct and inverse sides of the installation}

• Literary illustration of a garden of antiquity.

{According to Foucault, the garden serves as an early example of heterotopic space in the course of human civilization.}

• Dual narration {meta-narration of a narration}

Alternately alluding to both an interior and exterior perspective.

Does it reside in dream space?

TEXT.

Heterotopia.

There is an opening up ahead.

Overgrown, overlooked

{little choice now but to}

Enter/Exit.

smells of black soil after the rain.

Low-lying brush grows roughshod over the irregular path…

A breach of sunlight cuts through the canopy above.

{ka-lei-do-scope}

As the wind shifts and the trees sway heavy

The minutia of sound.

Omniscient.

Double-back or----- continue

behind/before

Through a hollow in the brush and

Across a ridge, no a sloping escarpment.

A fine mist hangs precariously low in a clearing be low, within/beyond the garden walls over which the wild grape runs riot; its fruit ripened by an early frost.

Along its reach, a valley of wildflower enclosed by a line of cypress.

Its stillness reigns over this majestic cacophony of color and vine.

It was mid-winter, and terribly cold, when the soldiers arrived at the gate. The gardener gave permission to cut down wood and not even to spare the best cedar or cypress. But the men could not bring themselves to fell these trees of which the size and beauty they so admired. Thereupon the gardener himself seized an axe, and cut down the tree that he thought the largest and loveliest, and the soldiers were no longer afraid to use the trunks that they needed, and to kindle the fires so they might endure the night.

Moving on,

interior/exterior

The path attenuates, the forest closing in, the light grows dim and the air feels thin.

All manner of wild creatures rustle unseen in the surrounding depths.

Covert. Unthreatening.

A little light now up ahead, a shallow egress in the thicket…

Dog hair on the pillow,

sand in the bed…

softly lie to the moonbeam overhead.

Leif Huron. 2010

Wednesday, October 20, 2010

The Male Gaze & Godard

Since beginning our exploration of Godard begin in September, I've both struggled and enjoyed the texts we've been reading. What has interested myself the most has been how he has portrayed and framed his female characters. One text that has entered into my mind during each of our viewings is Laura Mulvey's “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”. The male gaze is indulged in so many of Godard's films, for example the opening scene in “Contempt” the strip club sequences in “A Woman is a Woman” or even when we meet Patricia for the first time “Breathless”. These scenes happen before we've been able to have a relationship with these characters and they initially signify sexuality and are further defined by the men who need or desire them.

Anna Karina in "A Woman is a Woman"

Brigitte Bardot in "Contempt"

The women we have watched in “My life to Live”, “Breathless” and “2 or 3 things I Know about Her” appear to independent in the beginning, but slowly the curtain falls and we see they are searching for more and somehow their sexuality allows them to find salvation or a path to gain success. They are forced to be passive to achieve monetary gain, subjected consistently to be with a man in order to be a 'modern women'; whether it is paying rent, buying new clothes or getting a write an article for Herald Tribune.

The First time we meet Patricia in "Breathless"

Throughout our viewings in class, I also thought about how Hitchcock and Godard compare in their usage of female characters. Hitchcock, like Godard, places women in the passive role of the gaze. His women are always an image of perfection, never having to sell themselves for sex. The deepest moral falls usually involving murder or thievery. They rely on men for other reasons, to maintain a certain lifestyle, social success or to keep their fragile mental states in tact. When we meet the infamous heroines like Lisa Fremont "Rear WIndow", she is also defined by her sexuality and need for a man, we rarely see her in the movie without James Stewart's character. Godard allows his females to be anti-heroines. They fill the passive roles, though they do hold the ability to escape, they just never seem to get the chance to take the active role.

VM

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

2 or 3 things on Consumerism

Commenting on the film, Morrey notes that the one inspiration for Godard was a Le Nouvel Observateur report entitled “The Shooting Stars” about young women whom turn to prostitution in order to maintain their newfound consumerism. He goes on to offer that prostitution in the film can be seen as a metaphor for the condition of the consumer under an advanced system of capitalism.

Here is a letter (from the DVD booklet) in response to the article that I think crystallizes the point of view that Morrey is referring to. I also uploaded a few short clips from the film that speak to this as well.

Chris

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)